Innovations in Practice: Regenerative Agriculture In Oil Palm

In part 1 of the 2-part article, Wild Asia, a social enterprise, introduces tried-and-tested farming techniques to oil palm farmers to boost productivity as well as resilience and improve ecosystem health, using the ‘living lab’ approach.

MUHARRAM Sompo’s oil palm farm visitors are often struck by these first impressions – the lush vegetation and the cooler air.

Robust palm trees boast vibrant green fronds and red-orange palm fruits, with clumps of ginger plants intercropped between rows of trees. Pruned palm fronds are stacked neatly on the ground, speckled with microbe-rich worm castings. Healthy, mature salak (Salacca zalacca) trees take up one corner of the farm, whilst a DIY wooden compost bin heaped with farm wastes, livestock manure and food scraps sits at another corner. Unlike the hard, compact soil typically found in conventional farms, the ground feels bouncy underfoot.

This independent smallholder’s 1.2-ha farm in Sabah’s Kinabatangan District is the model farm, which embraces the WAGS BIO methods. The integrated farming approach prioritises soil health as well as biodiversity, and eschews synthetic pesticides and fertilisers.

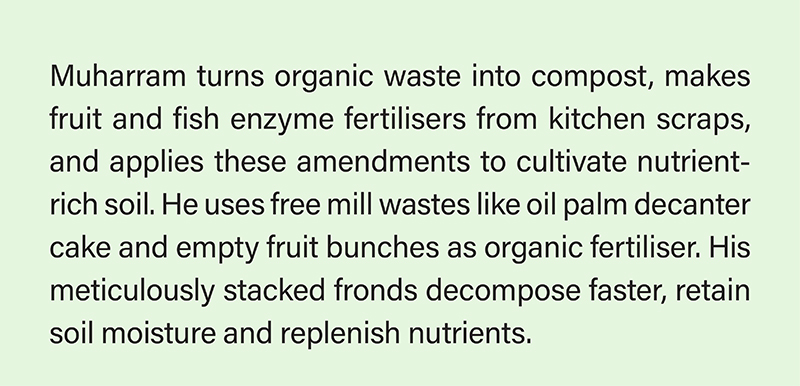

Oil palm fronds are processed into biochar and readded to the soil to boost fertility and sequester carbon. The salak fruits and ginger crops supplement his income and help improve farm biodiversity. Abundant worm castings are used as a natural fertiliser to grow pineapples, chillies, and brinjals in his home garden. These practices embody a closed-loop (agriculture) system that recycles all nutrients and organic matter material back to the soil it grew in, preserving the nutrients and carbon levels within the soil.

In short, Muharram works in concert with the natural systems and leverages cheap or free, low-tech solutions to produce optimal outputs whilst treading lightly on the earth.

“Since I started my BIO journey in 2019, my trees have become healthier, the palm fruits are denser, and my yields are fairly consistent,” says the MSPO (Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil) - certified farmer. His fresh fruit bunches (FFB) yield ranges from 24 to 27 metric tonnes per hectare per year, way above the national average of 16.70 tonnes (2024 Malaysian Palm Oil Board figures). Over the past five years, as the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) recommended, his yield has increased by almost 6%, even though his trees are at the optimal replanting age of 24 - 25.

“I’m not too worried about the bottom line because my production costs are low,” says the 43-year-old who has been adopting chemical-free farming for five years. “As long as my soil is healthy, my farm will remain productive in the long run.”

Organic Matter Matters

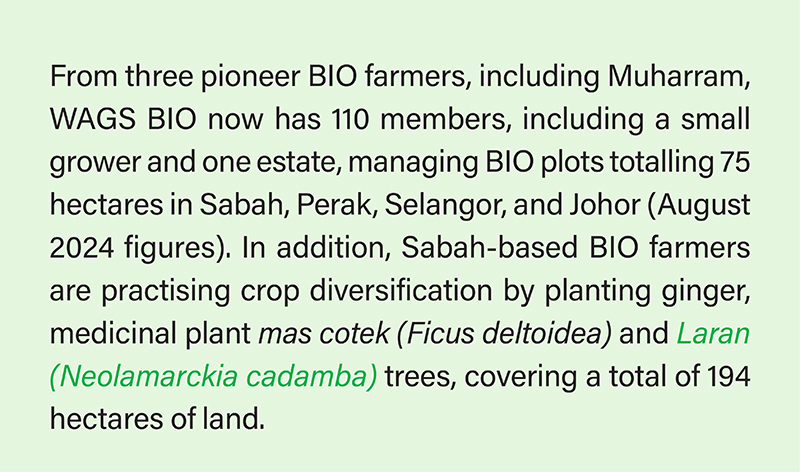

In 2019, Wild Asia kick-started WAGS BIO to help oil palm farmers switch from ‘conventional’ agriculture to chemical-free, regenerative agriculture. Conventional oil palm farming typically involves monocropping and the liberal use of agrochemicals, leading to degraded soil and decreased understory vegetation.

However, the seed for WAGS BIO was first planted in 2018 when WA initiated the ‘Living Soils’ project. At that time, WA had been working with farmers under the Wild Asia Group Scheme (WAGS) to help them meet international sustainability standards since 2012.

“We knew about organic farming, but it was almost unheard of in oil palm,” says Wild Asia Founder and Executive Director Dr Reza Azmi. “We started tapping into learnings from the past. Pioneers like Sir Alfred Howard understood that healthy, living soils are the key to combating pests and diseases in crops.”

Muharram is an independent smallholder who owns a 1.2-ha farm in Sabah’s Kinabatangan District.

Known as the father of the organic farming movement and the ‘champion of compost,’ Howard carried out experiments from England to India in the early 1900s. He established that organic matter, soil fertility, and plant health are intrinsically linked. A ‘living soil’ is a community of microbes that break down organic matter, which, in turn, supplies nutrients to the plants, resulting in healthier trees that are more resistant to diseases and pests.

Healthy living soils are the key to thriving, resilient crops.

“We gathered evidence for this (BIO) approach by studying natural farming practitioners and reading up on older literature and current scientific works in other fields,” adds Reza, who leads Wild Asia’s senior team of biologists, ecologists and biodiversity experts.

“At our first Living Soils workshop, we showed farmers the basic ingredients for healthy forest soils and taught them ways to improve soil health.”

The programme has since grown and evolved as Wild Asia explores innovative practices, tailors the farming approach to local contexts and tests them out on working farms. One of its main agendas is to help farmers build resilience to climate change and swings in palm oil prices.

Frond stack modification, one of the BIO routines Muharram adopted on his farm.

Learning by Doing

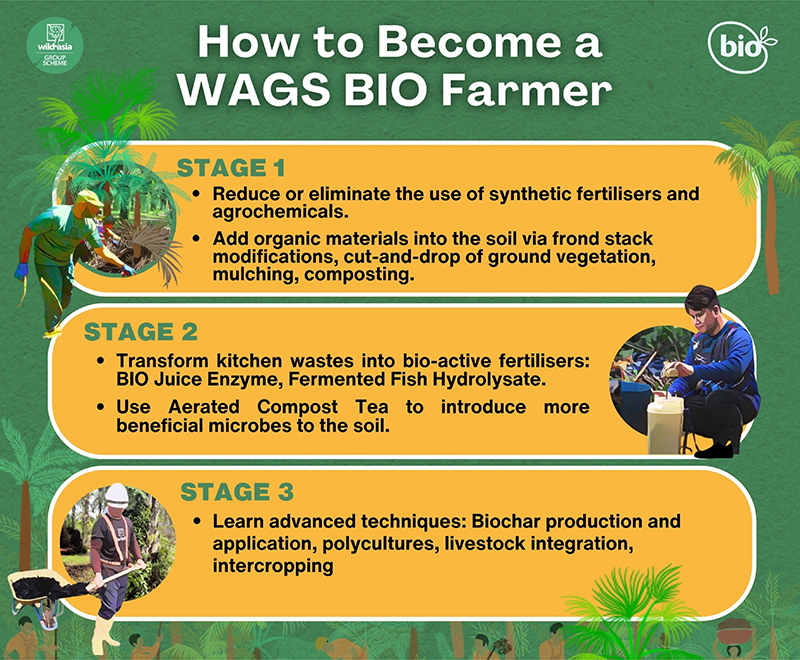

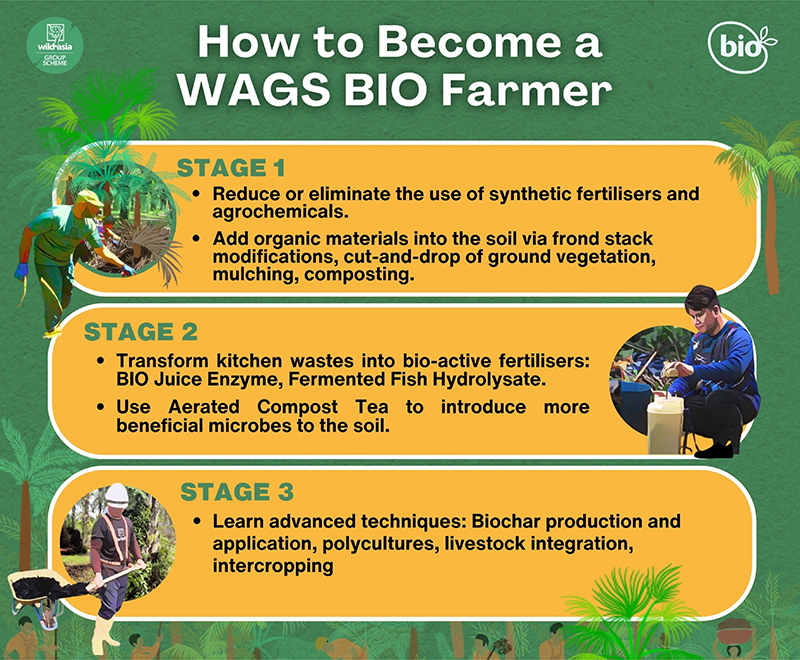

Structured in incremental stages, WAGS BIO is open to all WAGS members who are MSPO and internationally certified. The BIO adoption is gradual and based on each farmer’s skills, knowledge, interest and resources.

“Most of our work in West Malaysia is in collaboration with other organisations for specific research projects (SAN-Ferrero project),” says Wild Asia Director and Advisor Peter Chang, who oversees the WAGS BIO operations.

“In Sabah, most projects are supported by grants (e.g., Yayasan Hasanah, Borneo Orangutan Survival - Germany, Seventh Generation, and other SPIRAL partners) to further ongoing work, to grow projects like biochar and explore novel ideas like a low-energy composting system to bulk-produce compost.”

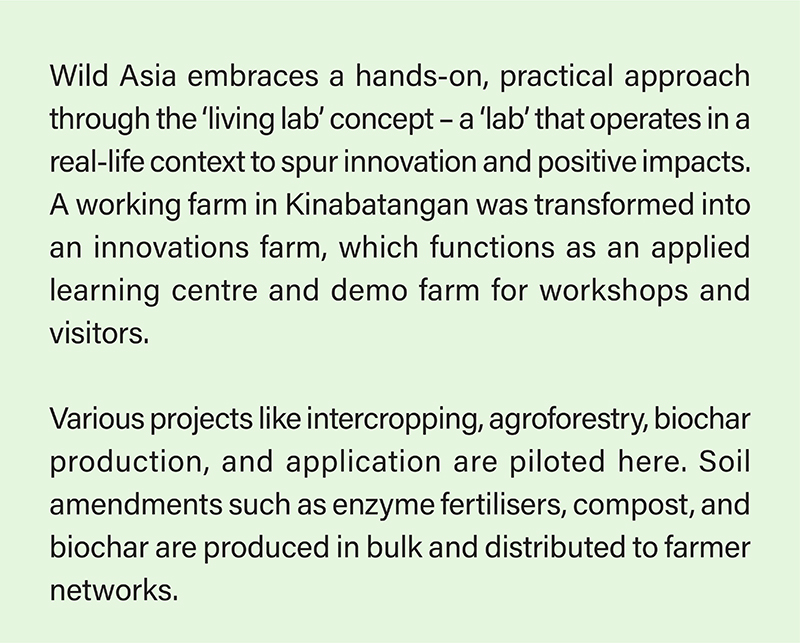

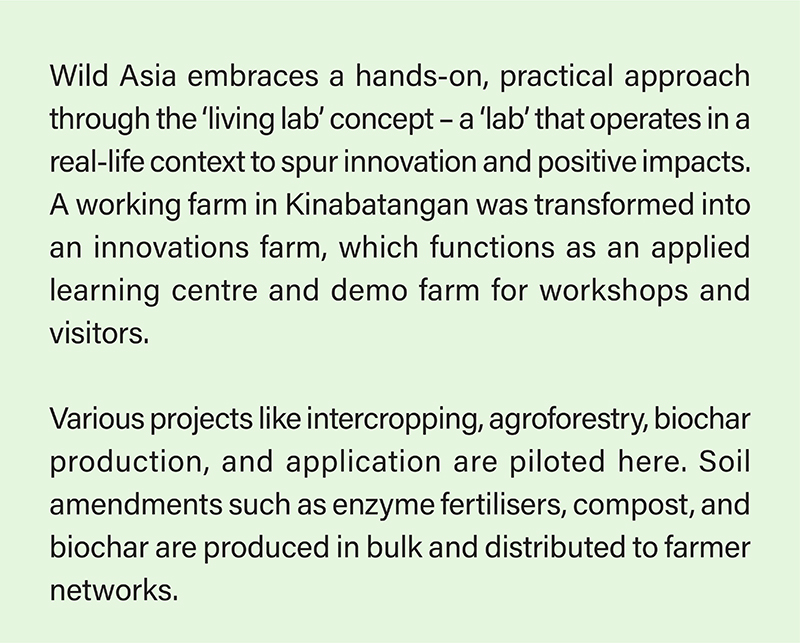

The ‘Living Labs’

Through regional hubs, Wild Asia’s dedicated BIO teams conduct community outreach and workshops to create awareness, teach essential skills and guide the farmers as they transition to regenerative practices.

Demonstration farms are set up on selected farmers’ plots for training and baseline monitoring activities.

“New BIO farmers get a three-month supply of enzyme liquid fertilisers to give them a head start,” says Chang. “Our target is to upscale the fermented fish hydrolysate and bio juice enzyme production to support up to 100 hectares of oil palm blocks annually.”

DIY enzyme fertilisers are a good substitute for synthetic fertilisers for farmers who lack resources.

“When Chang introduced me to WAGS BIO, oil palm prices hit an all-time low, and I had to cut expenses. Making my compost and fertiliser was a good alternative to weather the tough period,” says Muharram. Plus, reducing fossil fuel-based fertiliser use can be a climate solution.

Since he adopted BIO routines, from cut-and-drop and frond stacking to juice and fish enzyme applications, Muharram could see palpable results within months. Worm castings started popping up, indicating an increase in the earthworm population (WAGS BIO report 2023; p. 33-34). As nature’s tillers, earthworms aerate the soil by channelling through it. They feed on organic matter, and their castings put good bacteria, enzymes, plant nutrients, and organic matter back into the soil. The castings also improve soil porosity and water retention.

Perak-based BIO farmer Mat Jailani Arshad shaved off about RM4,000 from his annual fertiliser costs since he swapped synthetic fertiliser for homemade enzyme fertilisers on his 0.6-ha BIO plot. Wild Asia also uses his farm to produce enzyme fertilisers in bulk for BIO farmers in Perak.

“Since I stopped using chemicals and planted beneficial flowering plants for natural pest control, my farm is thriving with insects like beetles, wasps, bees and grasshoppers,” says the MSPO-certified smallholder, also an exemplary BIO farmer. Before joining WAGS BIO in 2021, Mat Jailani stopped using pesticides when raising livestock like cattle, goats, ducks and geese. He discovered that the grazing livestock helped control weeds and nourish his soil.

“After I sold my cattle and goats, I continued chemical-free farming to keep the momentum going. It has been seven years now. My palm trees are healthy, and my yields are consistent,” says the 60-year-old, who regularly hosts university students who do insect surveys on his farm.

Mat Jailani Arshad is a Perak-based BIO farmer who has swapped synthetic fertiliser for homemade enzyme fertilisers on his BIO plot.

Intercropping Benefits

The BIO team also germinates ginger seedlings for farmers to intercrop with oil palm.

So far, 40 BIO farmers have embraced ginger intercropping with varying outcomes. On his first attempt, Muharram produced a bumper crop of nearly 100 kg of ginger.

“My challenge was trying to sell a huge volume of ginger for the first time,” he adds, chuckling. However, his subsequent harvests were not as bountiful due to several factors, such as seasonal floods and types of composts.

“One lesson we learned from this intercropping experiment is that due to intense competition for nutrients, the oil palm roots stunted the growth of ginger rhizomes,” says Chang. Consequently, the ginger sizes were small and did not meet commercial standards, thus lowering the sale price.

“We’re now looking at growing ginger in bags lined with plastic sheets. Upon harvesting, the organic materials in the bags can be spread around the oil palm trees as mulch and nutrients for the soil.”