Innovations in Practice: Building Resilience in Smallholder Farmers (Part 1)

Beyond helping independent smallholders boost sustainable oil palm production, Wild Asia empowers them through alternative income-generating enterprises.

Building Resilience

When Nisa Usman signed up to join the Wild Asia Group Scheme (WAGS), she never imagined she would one day grow organic vegetables to feed her family, make extra income from other enterprises, and earn the “mushroom entrepreneur” moniker.

In 2017, Wild Asia extension agents visited Nisa’s village, Kampung Paris, Kinabatangan District, Sabah, to offer free training aimed at helping independent smallholder farmers improve their farm management practices and meet sustainability standards.

A two-hour drive from Sandakan, Kampung Paris has a population of approximately 700, comprising the indigenous Orang Sungai. Nisa’s family cultivated cocoa, rice, and corn for subsistence before switching to oil palm in 2000.

Then, a young mother of four, Nisa, inherited the 5-ha family farm in 2003. As full-time oil palm farmers, she and her husband did all the work – from weeding and pruning to harvesting. Through WAGS, they learned to farm sustainably and reduce operating costs by reducing chemical inputs. Within a year, she gained her international sustainable certification.

With only a primary school education and few other skills, Nisa relied solely on her oil palm income and was subjected to the capricious fluctuations of palm oil prices. When Wild Asia introduced the WAGS BIO initiative in 2020, Nisa seized the opportunity to acquire new skills. A production system designed to help farmers adopt regenerative farming practices, WAGS BIO strives to demonstrate that profitability and environmental sustainability can coexist.

“I signed up (for BIO) not knowing that it would open doors to extra revenues and benefits,” says Nisa, whose plantation received Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification in 2019.

Nisa grows an abundance of cucumbers in her home garden, which she learned about under a Yayasan Hasanah Special Grant project managed by Wild Asia in 2020.

She learned to make compost, fruit-based enzymes, and fertilisers from fish waste, kitchen waste and farm wastes to create microbe-rich soil for her palm trees. In 2020, under a Yayasan Hasanah Special Grant project managed by Wild Asia, Nisa learned to grow a home garden. She received free farming tools, including mesh netting to protect her seedlings, a water tank, and a hose for irrigation on the farm.

“Thanks to BIO training, I have created a thriving organic garden that yields fresh, pesticide-free vegetables for my family,” adds Nisa, who planted on a modest 6-sqm plot and applies DIY enzyme fertilisers on her home garden. Her bountiful harvest of cucumbers, luffa, brinjals, and okra was more than enough to feed her extended household of ten. Under another BIO initiative, Nisa intercropped oil palm with ginger and made RM480 from her first two harvests.

“We shaved off about RM300 from our monthly food expenses since we started the home garden.” But it was the mushroom cultivation venture that harnessed her entrepreneurial streak.

Wild Asia roped in a mycology and plant pathology expert, Dr. Rakib Rashid from Universiti Malaysia Sabah’s Faculty of Sustainable Agriculture, to teach farmers on mushroom cultivation, providing them the opportunity to earn supplemental income. Wild Asia connects farmers with mushroom block suppliers to obtain wholesale pricing and facilitates the delivery of the blocks to farmers. Nisa started with an initial 200 mushroom blocks. Within two weeks, she had her first harvest, sold the mushrooms, and made a gross profit of RM1,000.

“I was surprised at how easy it was to maintain the mushroom blocks. We just need the right temperature, humidity, air flow and lighting conditions for them to flourish,” says the 49-year-old. Encouraged by the results, Nisa designated a fixed space in her house for her mushroom venture.

Each mushroom block has a lifespan of about three months and can produce six to seven harvests. Three years on, she still grows an average of 350 to 500 mushroom blocks, earning a net profit of about RM2,000 to RM3,000 for each harvest. Aptly, her local community labelled her as usahawan cendawan (mushroom entrepreneur).

“The Ripple Effect

Nisa is one of 203 WAGS BIO farmers across Malaysia and Thailand who are directly and indirectly reaping the benefits of these alternative income-generating activities.

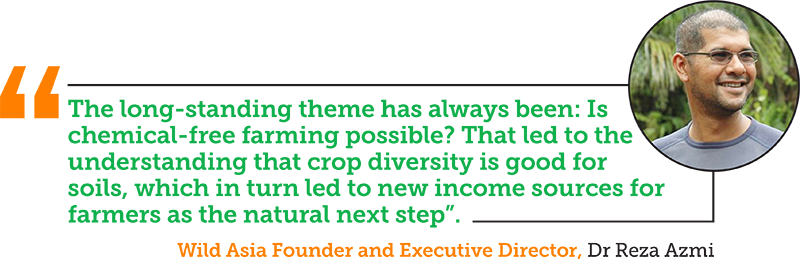

Back in 2019, when Wild Asia sketched out the blueprint for the BIO programme, income diversification was not spelt out in the agenda. The big picture is about helping farmers adopt regenerative farming practices, improve their livelihoods, and foster resilience.

Farmers who adopted natural farming practices for their oil palm blocks would then apply their newfound knowledge and skills at home, yielding extra earnings.

Smallholder farmer Norella Ambang has tended a home garden since young. The mother of five grows a variety of vegetables and fruits for her family’s use. However, through BIO workshops, the Sabah-based farmer discovered wholesome alternatives, such as making DIY organic fertilisers and natural pest control methods.

“I’d look up farming tips on the Internet, but nothing beats hands-on learning through practical workshops,” says the MSPO-certified smallholder who owns a 4.8 ha oil palm farm. “It’s heartening to feed my family organic food that is rich in nutrients, low in pesticide residues and delivers spin-off environmental and social benefits.”

Her organic chillies, whipped into sambal (a relish) and sold to colleagues and friends, are a perennial bestseller. An avid social media user, Norella shares her farming journey on TikTok and Facebook, inspiring her followers to adopt organic farming practices.

Eclectic Enterprises

In Sabah, enterprising offshoots from BIO programmes that could generate alternative income for farmers include Laran (Neolamarckia cadamba) tree intercropping, Mas Cotek (Ficus deltoidea) cultivation, biochar production (through carbon credits) and a low-energy composting system to bulk produce compost.

“We brainstorm for ideas within WA and with our farmers, and tap into our collective experiences and expertise. Then, we test out the ideas on working farms,” adds Wild Asia Director and Advisor Peter Chang, who oversees the WAGS BIO operations.

Nisa intercrops oil palm with ginger, generating additional income through her bountiful home garden harvest.

“In 2020, ginger was sold at RM8 per kg; now the price is RM20 per kg. Laran timber has a high commercial value. And we found a factory that processes Mas Cotek into herbal products, and they are willing to purchase the harvest from our farmers”, says Chang.

For the mushroom venture, the number of farmers who want to grow mushrooms commercially is kept to two farmers per area, to avoid saturating the market.

Innovative Compost Method

In early 2024, Chang and his team established a novel composting system, known as the Cascading Compost System (CCS). The conventional method for making compost requires turning it every two weeks or once a month to allow organic waste to decompose properly.

Stacked like three-step stairs, a cascading compost system (CCS) is a low-energy composting method that does not require heavy machinery or intensive labour.

Using a cascading system, the compost ‘bins’ are stacked like three-step stairs. At the topmost bin, a layered mix of grass, woody shrubs, leaf litter, and elephant dung is left to decompose for a month, then manually transferred to the next bin below, and the lowest-level bin in the following month. A specially designed irrigation system helps to sprinkle DIY enzyme fertilisers and water on the compost every three days. The wooden bins include mesh wire panels to provide more aeration.

The CCS method was established by Chang and his team in early 2024.

“All the organic materials are gathered from the farm, and we collect the elephant dung from the nearby Borneo Elephant Sanctuary, but any easily available livestock manure would do. It’s a low-energy composting method that does not require heavy machinery or intensive labour,” Chang explains.

The CCS can produce an average of five to seven cubic metres of compost per month. A rotary sieve drum is used to separate the compost into fine and coarse compost. The coarse compost can be used on the oil palm plots, whilst the fine compost can be packaged and sold as organic compost for vegetables and potted plants.

“We’re also looking at using the compost in different ways, like making a biochar compost mix or mixing it with mill wastes. The CCS can also be a potential enterprise for farmers to generate additional income,” says Chang.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of the Innovations in Practice series, which will be released in the next PalmSphere edition.